In the summer at Antarctica’s McMurdo Station, from late October until late February, the sun stays above the horizon 24 hours a day — a phenomenon known as the Midnight Sun. Conversely, the Antarctic winter — or Polar Night — delivers four months of complete darkness save for the light of the aurora and stars. Further inland at the South Pole, the seasonal effect increases, with more continuous light over summer and more continuous darkness over winter.

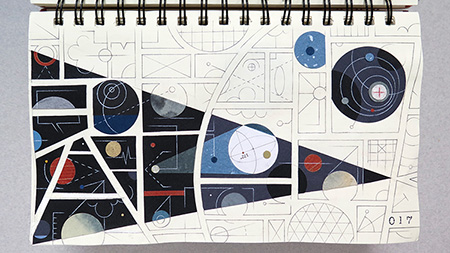

The seasons are a result of the Earth’s tilt in relation to the sun. While the tilt’s direction never changes, different parts of Earth are exposed to direct sunlight as we orbit the sun. In the summer, Antarctica is on the side of our planet that is tilted toward the sun, therefore receiving continual sunlight. During winter, Antarctica is on the side tilted away from the sun, depriving it of the sun’s rays.

For Antarctic residents, months of continuous sunlight can be disorienting. During my summer visit, my circadian rhythm shifted markedly without the cue of evening darkness. Becoming increasingly sleep-deprived, I strove to sleep by the clock rather than light in an effort to get back on schedule. A month later, it still felt odd to head to the bunk in broad daylight for a “full night’s” rest.

A greater challenge is wintering over in darkness. This is undertaken annually by about 150 personnel at McMurdo and another 50 at the Pole. They commit to stay the entire 4-5 month duration since flights don’t operate in Antarctica during the winter. (Temperatures dip below -50 degrees Fahrenheit, freezing gasoline and aircraft hydraulics.)

The most prominent winter health concern is depression, well-known in parts of the globe that experience extended periods without sunlight. As a result, prospective Antarctic workers are screened for seasonal affective disorder. Past that, much pivots on the composition of the crew from year to year and the chemistry between them.

Under most circumstances, a healthy, supportive community flourishes amidst a season of shared experience and camaraderie. For a hardy few, activities such as the 300 Club offer the opportunity to bask in a 200-degree sauna, followed by running outside in nothing but shoes when the outdoor temperature falls below -100 degrees. The immediate objective: to endure a temperature swing of 300 degrees Fahrenheit. The larger objective: To collectively celebrate and embrace the continent’s natural offerings.

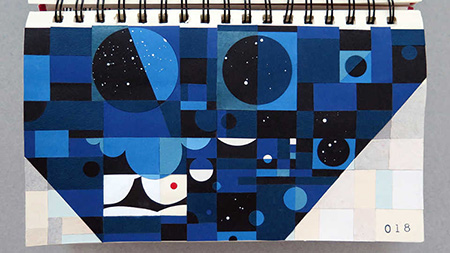

Antarctica’s celestial show ranks high among these. Katy Jensen, a South Pole overwinterer, recalls for the Atlantic: “After sunset in March, there’s about a month of gradually darkening twilight, so every day you can walk outside and see more stars than you saw the day before. The moon is up above the horizon for two weeks at a time, so you swear you can watch it change phases.”

In the same article, we learn that if a full day is the time between two sunrises, a full day in the South Pole lasts approximately 8,760 hours (24 hours multiplied by 365). This is because at the Pole, the sun rises just once a year and sets many months later.

So, is it a new day when you wake at the Pole? In your mind, yes. But in reality, only once a year.